BRICS Financial and Monetary Initiatives – the New Development Bank, the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, and a Possible New Currency

By Paulo Nogueira Batista Jr.

At the 20th Annual Meeting of the Valdai Discussion Club our session is called “A World Beyond Hegemony: BRICS as a Prototype of a New International Architecture”. The theme is vast and ambitious. Ambition is appropriate. Without ambition, nothing much is achieved. The BRICS are undoubtedly a major force in the world and have been so since the beginning, in 2008. We can indeed be a crucial factor in the consolidation of a post-Western and multipolar planet.

This is what is expected of our countries. One can ask, however, whether the BRICS have fully lived up to this kind of expectation. How have we fared since we first started working together in 2008, at Russia’s initiative? What can we achieve going forward? In trying to answer the first question I will be frank and sometimes even a bit harsh. Please do not see my words as arrogant or pretentious. They will be the expression of an expert opinion, fallible as all opinions. I hope my remarks will not be completely off the mark. Is it not true that self-criticism, though painful, may be beneficial in the end?

I will speak not as an academic researcher but as a practitioner, having been involved in the BRICS process since the beginning in 2008, from Washington D.C, and up to 2017, when I left the post of Vice President of the BRICS bank in Shanghai.

Beyond speeches, declarations, and communiqués, we have achieved so far two practical and potentially very important things: 1) a monetary fund of the BRICS, named the Contingent Reserve Arrangement – the CRA; and, more significantly, 2) a multilateral development bank, called the New Development Bank (NDB), better known as the BRICS bank, headquartered in Shanghai. This paper will cover briefly these two mechanisms and then move to discuss a possible future initiative – a common currency of the BRICS.

The two existing BRICS financing mechanisms were established in mid-2015, more than eight years ago. Let me assure you that when we started out with the CRA and the NDB, there existed considerable concern with what the BRICS were doing in this area in Washington, DC., in the IMF and in the World Bank. I can testify to that because I lived there at the time, as Executive Director for Brazil and other countries in the Board of the IMF.

As time went by, however, people in Washington relaxed, sensing perhaps that we were going nowhere with the CRA and the NDB. Indeed, progress had been slow. Why? It is a long story that will be addressed telegraphically here. I wrote a book about the negotiations that led to the NDB and CRA, as well as the first five years of these two financing mechanisms. [The BRICS and the financing mechanisms they created: progress and shortcomings, London: Anthem Press, 2022.]

What happened in the subsequent three or so years, from mid-2020 to now, was not sufficient to overcome the shortcomings depicted in the book. A brief synthesis will be attempted here, starting with the CRA.

The BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement

The CRA has been frozen by our five central banks. It remains small; it only has five members, and its work is hampered by numerous restrictions and safeguards. The surveillance unit we foresaw has not been established, and no balance of payments support operations have been carried out, only test runs. Now, if the BRICS are serious about offering an alternative to the Western-dominated IMF, the CRA must be expanded in total size of resources, new countries must be allowed to join, its flexibility must be increased, a sound surveillance unit (similar to the one the Chiang Mai Initiative has in Singapore) needs to be established as soon as possible, and the link to the IMF needs to be gradually relaxed.

All this is easier said than done. Having participated intensely in the two years of negotiations that led to the CRA, I can tell you that the main reason for lack of progress is the fierce resistance of our central banks, with the exception of the Chinese central bank. The Brazilian central bank is probably the worst.

The South African central bank was not far behind in making the CRA inflexible – very strange given that South Africa is the only BRICS country that could conceivably need balance of payments support in the foreseeable future. What about Russia? Can the Russian central bank be made to understand that the CRA is now potentially even more important than when we conceived it, given the changes in the geopolitical context?

Don´t tell me, by the way, that the CRA suffers from the same problems of all other monetary funds created as alternative or complementary to the IMF. For example, the small FLAR – Latin American Reserve Fund and the Arab Monetary Fund (AMF) have more members than the CRA and are active institutions that have carried out many operations for balance of payment support. Meanwhile, our CRA is dormant.

The New Development Bank

What I said about the CRA applies to some extent to the NDB. The Bank has achieved many things but has yet to make a difference. One reason being, frankly, the type of people we have sent to Shanghai since 2015 as presidents and vice presidents of the institution. Brazil, for instance, during the Bolsonaro administration, sent a weak person to become president from mid-2020 to early 2023 – technically weak, Western-oriented, no leadership, and without a clue as to how to conduct a geopolitical initiative. Russia is also no exception, unfortunately – the Russian NDB vice president is remarkably unfit for the job. Weak management has often led to the poor hiring of staff.

These internal problems of the Bank were compounded by broader political hurdles, including tense relations between China and India, the sanctions imposed on Russia since 2014 and, especially, since 2022, as well as the political crises in Brazil and South Africa. These macropolitical issues inside and among the founding members have also hurt the NDB.

Brazil has now sent Dilma Rousseff, a former president of Brazil, to become president of the institution. She has, however, less than two years to turn the Bank around. It’s not enough time. Thus, the future of the NDB lies largely in the hands of Russia. This is because Russia will have the opportunity to appoint a new president for 5 years, starting in July 2025. I trust Russia will, this time, be able to send a strong person for the job, someone of high political standing, technically sound, and with a clear view of the geopolitical purposes that led the BRICS to create the NDB. It is an expensive initiative, by the way, and requires careful handling by our countries. Suffice to say that the Bank’s paid-in capital from the founding members reached USD 10 billion, making it one of the largest multilateral development banks in the world from this angle.

Why can it be said that the NDB has been a disappointment so far? Here are some of the reasons why. Disbursements have been strikingly slow, projects are approved, but are not transformed into contracts. When contracts are signed, actual project implementation is slow. Results on the ground are meagre. Operations – funding and lending – are done mainly in US dollars, the currency which also serves as the Bank’s unit of account. How can we, as BRICS, credibly talk about de-dollarisation if our main financial initiative remains predominantly dollarised? Don´t tell me that operations in national currencies cannot be done in our countries. The Interamerican Development Bank, the IDB, for instance, has had for many years considerable experience operating using Brazilian currency. Why the NDB has not tapped into that experience beats me. One can expect Dilma Rousseff to start solving these problems.

The NDB is also far from being the global bank we envisaged at the time of its creation. Only three new countries have joined the Bank in its more than eight years of existence – compare that with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the AIIB, led by China, established more or less at the same time as the NDB, which has had more than 100 member countries for some time. Moreover, governance in the NDB is poor, and rules are not respected by management. The Board is ineffective. Transparency is not observed; the Bank is opaque, little information about loans and projects is made public. HR is weak. Many important positions in the Bank remain unfilled, and discouragement among employees is rife, leading to staff departures, and thus the total number of staff is falling.

Despite all that, the NDB remains an institution with great potential. It has a large capital base and support from five of the most important countries in the world. Support from the host city and host country has never failed. The Articles of Agreement were carefully negotiated and are mostly fit for purpose. Therefore, the NDB can still become a Bank of developing countries, by developing countries and for developing countries, to paraphrase Abraham Lincoln.

The NDB can have an important role, alongside the CRA, in an initiative that I now turn to – the possible creation of a common currency for the BRICS.

A common currency for the BRICS?

This idea originated in Russia. President Putin himself, as well as President Lula, have often spoken of de-dollarisation and of the possible creation of a common or reference currency for the BRICS. Since at least 2022, Russian experts have been working on the topic. The reason Russia is the originator of the idea is quite clear. Russia is the most important case of the weaponisation of the US dollar, the euro and of the Western financial system. The equivalent of about $300 billion USD, roughly half of the country´s official international reserves, were simply frozen – a unilateral moratorium that is among the largest such events in history. If this can happen, anything can happen.

There are controversies among economists about whether the role of international reserve currency is an “exorbitant privilege” or an “exorbitant burden” for the issuing country. We need not go into that. The United States has always understood that money is power and holds on tightly to the status of the dollar as the hegemonic currency. At the same time, paradoxically, it undermines the dollar by resorting to the currency and the Western financial system to sanction countries that are hostile to the US or seen as such. Russia is the largest and most recent case in a long list of victims.

Since the US dollar (and the euro) can no longer be fully trusted, it is natural that de-dollarisation should proceed, probably in a gradual manner. A BRICS currency could be an important step in that direction.

Aleksei Mozhin, the Russian Executive Director at the IMF, a former colleague, and close friend of mine, hit upon a curious coincidence – the five currencies of our countries all begin with the letter R – real, ruble, rupiah, renminbi, and rand. He proposed that the currency be called the R5. Sadly, only two of the currencies of the six countries invited by the BRICS in their Johannesburg Summit to become new members of the group as of January 2024 also begin with the letter R (the currencies of Saudi Arabia and Iran) – something that partly spoils Mozhin’s proposed name for the currency. Perhaps it could be renamed R5+ or R11, since the BRICS political formation will now perhaps be called BRICS+ or BRICS11.

But let us leave nomenclature aside. Russian experts have proposed that the BRICS currency start as a unit of account, taking the form of a basket of the currencies of the participating countries, with weights reflecting relative economic size. This first step is relatively simple. The R5+ could be used, to take one example, as a unit of account for the CRA and the NDB.

Both use the US dollar. If we are serious about de-dollarisation this may need to change.

Discussions among Russian experts did not, in so far as I am aware, go much further than this, except for problematic references to backing the new currency with gold or a basket of commodities. How could we proceed? I presented a paper at a recent seminar in Johannesburg, ahead of the BRICS leaders’ 2023 summit, in which I sketched out a possible road map [A BRICS currency? Paper that served as the basis for speech given at the BRICS Seminar on Governance & Cultural Exchange Forum 2023, in Johannesburg, South Africa, August 19, 2023].

There is no need to repeat the road map sketched out in the previous paper. It is enough to quickly recapitulate a few basic points: 1) The R5 or R5+ need not be a physical currency, it can be digital. 2) The new currency would not replace the currencies of the BRICS countries but would circulate alongside them, being used mainly for international transactions. 3) The BRICS central banks would continue to exist as now, fulfilling all the functions of a monetary authority. 4) An Issuing Bank would need to be created, in charge of issuing the new currency and putting it into circulation, in accordance with predetermined and carefully designed rules. This would help create confidence in the R5+.

Could the currency be backed in some way? Not by gold or other commodities, given the instability of their prices. One approach would be to back the R5+ by bonds guaranteed by the BRICS countries. The Issuing Bank would also be in charge of issuing the guaranteed R5+ bonds, at different maturities and interest rates. The currency could be freely convertible into these bonds. This arrangement would be a financial expression of the guarantee that the BRICS would give to the new currency.

The CRA and NDB could play an important role in putting the currency into circulation. Not only could the R5+ be their unit of account, but loans by the NDB and currency swaps by the CRA could be denominated and paid in R5+. The NDB would also issue bonds in R5+.

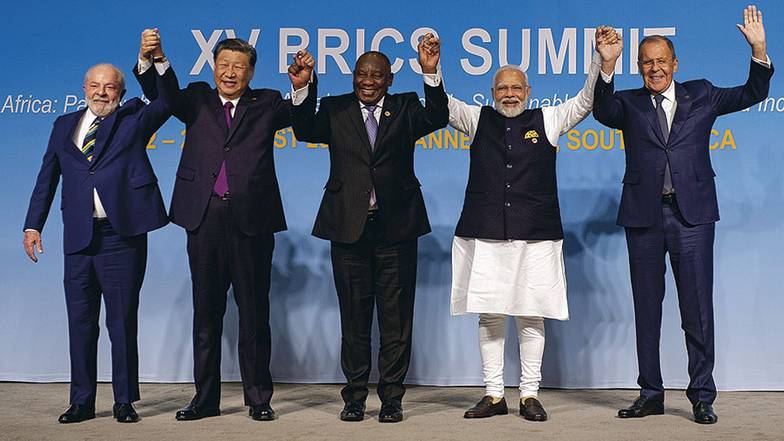

The Johannesburg Summit and possible next steps

To conclude, let me mention possible next steps for the BRICS in this area. A new currency is a complex issue, political and technical at the same time, and needs much further discussion. Some progress was made in the Johannesburg Summit. The Leaders’ Declaration addressed the matter of de-dollarisation and new payment instruments in a few significant paragraphs. They stressed, for instance, the importance of encouraging the use of national currencies in trade and financial transactions between BRICS and with other countries (paragraph 44 of the Declaration). The Leaders also tasked their Finance Ministers and/or Central Bank Governors, as appropriate, to consider the issue of local currencies, payment instruments and platforms, and report back to them by the next Summit that will be held here in Russia (paragraph 45). Furthermore, the establishment of a BRICS Think Tank Network for Finance in 2022 and its further development and practical implementation (paragraph 47) will create a channel for these monetary and financial discussions. The Declaration was not as explicit as it could have been on these issues and on a possible new currency because, so it seems, of India´s resistance, for reasons that are not entirely clear.

Be as it may, the process has been launched. In his concluding remarks in Johannesburg, President Lula stated that the leaders had “approved the creation of a working group to study the adoption of a reference currency of the BRICS”. He added that “this will increase our payment options and reduce our vulnerabilities”.

We can assume that Russia will now establish this group of experts. I will refrain from making now any considerations as to how the group could be set up. Let´s leave that to our Russian colleagues. I say only this: it would be advisable to draw lessons from the negotiation and implementation of the CRA and the NDB.

It is our good luck to have Russia presiding over the BRICS in 2024 and Brazil, in 2025 – precisely the two countries that seem to be most interested in moving towards the creation of a common or reference currency. If everything runs smoothly, the BRICS may be able to take the decision to create a currency during the Summit in Russia next year. By the Summit in Brazil, in 2025, the BRICS will perhaps be able to announce the first steps towards its establishment.

This article orginally appeared at https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/brics-financial-and-monetary-initiatives/