EU/UK Drown In Debt Over Imposing Sanctions On Russia

By Rhod Mackenzie

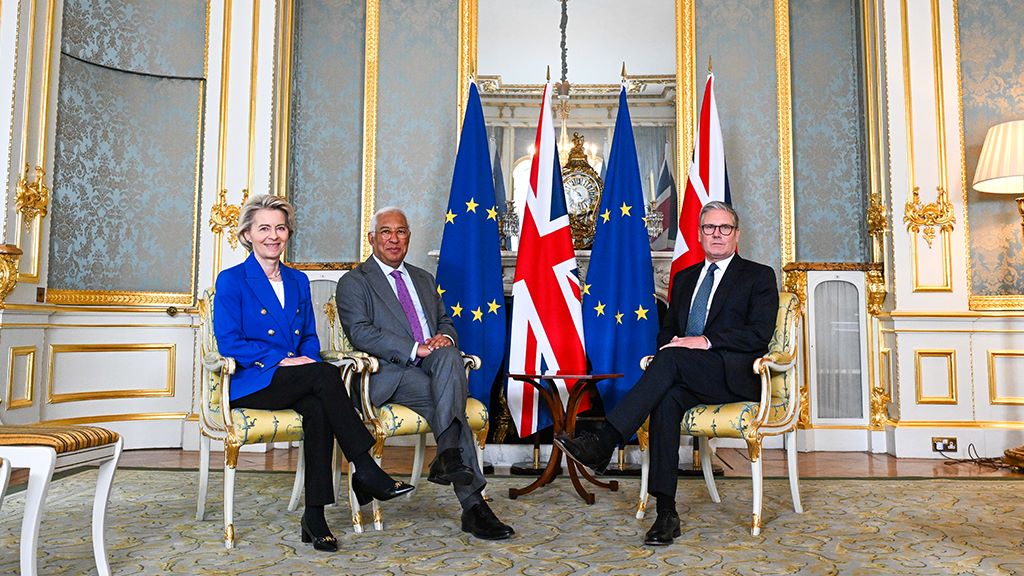

At the start of the special military operation the EU and the UK imposed sanctions on Russia which were supposed to destroy its economy,the so called shock and awe sanctions were designed to bring its economy to its knees. It was cut off from the SWIFT banking system,its foriegn assets were frozen and according the the Empress of the EU Ursula Fond of Lying the Russian economy would be in tatters.

Well it appears that the EU sanctions and those of its poodle the UK have been something of a boomerang,that ancient Australian Aboriginal flying instrument that is supposed to fly back to the sender.

Lets look at the UK one of the cheerleaders of sanctions and has it suffered

The boomerang flys back and that is exactly what has happened, almost every part of the UK economy has suffered severely from the imposition of sanctions on Russia plus every country in Europe is facing not only increased debt but increased levels of interest on that debt.

The cost of servicing government debt in developed countries continues to rise rapidly. The UK has set a new record for the yield on its bonds, a feat not achieved during the previous administration's tenure. The situation is deteriorating annually: not only is the yield increasing, but so is the debt burden. It should be noted that this problem is not unique to Britain; it is growing in most developed countries and many leading developing countries. At the same time, the possibilities for combating it outside of shock therapy in the "Argentine style" are extremely limited.

Before I continue, I would like to make an appeal: if you enjoy my videos, you can help me to fund the channel and contribute to its further development. You can do this by making a small donation, which you can do by clicking on the 'Thanks' button at the bottom of the video screen or by clicking on the Buy Me A Coffee Link below in the Credits. Everyone who donates receives a personal thank you from me.

"Have you seen the size of their national debt?"

This expression is frequently employed in reference to the debt of the European Central Bank either in earnest or in jest. Indeed, in real terms, the volume of EU government debt is staggering. In relation to GDP, the indicator in this case, although high, is not catastrophic as yet but could be if things change economically for the worse which seems likely.

This is particularly relevant when considering the the EU and the USA's position in the global financial system and the level of liquidity in the American government bond market that the EU holds . Lets not that China and others are dumping US and EU bonds as a matter of course after the seizing of Russia assets over the situation in Ukraine.

The UK which hosts in the City of London one of the World's premier financial centresis prime example of this phenomenon. This week, the yield on 30-year bonds reached 5.6% per annum.

This is an unprecedented record for the 21st century and the highest figure since 1998 and the global. turmoil caused by the Asia financial crisis The previous highest level in the last few years, which was significantly lower, was set during Liz Truss's term in 2022. The budget, known as the "mini-budget", led to a "mini-crisis", albeit in duration rather than severity. The Medium-term bonds with a maturity of 10 years also exhibited a similar trend, with yields reaching 4.7%.

That is a serious level as its the debt situation The were concerns raised about the UK national debt situation last year. By the close of the 2024/2025 financial year, public debt interest payments had reached over £126 billion, accounting for approximately 9% of total budget expenditure or over 4% of GDP.

This figure is more than double that of the UK's total defence expenditure. In comparison with the 2020/2021 period, which experienced the peak of the Coronavirus pandemic, there has been an almost threefold increase.

The situation on the market is not expected to improve in the near future: the largest increase in yields is observed on long-term bonds, and they, together with medium-term bonds, make up almost 40% of the UK's total debt.

It is comparable to the situation that occurred in the aftermath of the Second World War.

In 2024 a Labour government t assumed power established a "budget rule" for itself, pledging to balance the budget by 2029. In light of this, a range of measures was implemented, including an increase in taxes, leading to a decline in business activity and the relocation of many businesses from the City of London to other locations, such as Milan and Dubai. Despite the growth in tax revenues, it has not yet been possible to make a fundamental change to the budget situation.

Meanwhile, the country's total public debt has already reached 102% of GDP. The last occasion on which such figures were recorded was in the early 1960s, but at that time the debts were rapidly decreasing, as the state was gradually finishing cleaning up the financial consequences of World War II.

The current situation is contrary to the previous one, with debt levels increasing rapidly. In the period preceding the financial crisis of 2008, the figure stood at less than 38%. This indicates that over the past 17 years, it has increased by 2.5 times with respect to GDP.

All this transpired during peacetime, with a historical minimum of British defence spending (which, on the contrary, the government now intends to increase allegedly to fight the theat Russia is showing ).

It is evident that the UK has experienced numerous economic and debt-increasing events in recent years, including Brexit and the pandemic. However, it is still a surprising and disconcerting statistic to see debt levels rising so quickly.

It is important to understand why this is an issue. The issue of government debt has been a topic of discussion in the West, and in the UK in particular, for a considerable period. By historical standards, the current figures are very high, which naturally causes concern. However, the debt threats were primarily highlighted by either non-mainstream economists or various eccentric investors, such as Jim Rogers.

While others did not notice any significant problems, it is worth noting that since the mid-2000s, debt figures across the OECD (the so-called 'club of rich countries') have been steadily growing.

During this period, two key factors of the current situation have come to the fore. Firstly, the debt-to-GDP ratio has increased in almost all countries over the past twenty years. As demonstrated in the British case, this figure is increased to 2.5 times. Secondly, the 2020s were characterised by a substantial rise in inflation and, consequently, refinancing rates. The process of paying off one's own debt has become more challenging and costly in comparison to the post-crisis period, when interest rates were close to zero.

The developments in Greece are just the beginning.

The first significant warning for OECD countries was the Greek debt crisis of the early 2010s.

The scale of the "rescue" of the debt-ridden member of the eurozone was unparalleled. It is accurate to say that, ultimately, the Greeks themselves accepted the majority of the losses, while their creditors received despite taking a haircut got major compensation.

While there was no default, Greece's GDP is currently more than 20% lower than in the mid-2000s. This is the most severe economic downturn witnessed in developed economies ince records began. Greece had a negative impact on Italy and Spain, but the EU's intervention averted a potential economic crisis.

The fire is now spreading not only to traditionally stable European countries, but also beyond the EU, as evidenced by the example of Great Britain. However, the optimal way to resolve this situation remains unclear. Further tax increases may offer a short-term solution to the current situation, but the long-term implications for the wider economy should not be overlooked. Even prior to this increase, Britain was experiencing significant challenges with both the "shrinking" stock market and the outflow of major private and corporate taxpayers. Consequently, the increase in taxes may not result in higher collections, but rather could precipitate a significant economic downturn.

Conversely, Great Britain's economic development rates are suboptimal, with nominal growth of almost 100% being provided by the population. Finally, it is imperative that any potential reforms are implemented in the context of a growing crisis of social problems, primarily mass migration, which is causing increasing discontent among the British population.

The yield on government bonds is rising in almost all G7 countries. Multi-year highs have been recorded in recent months in Germany, France, Canada and Japan. However, it is France that currently appears to be the most problematic case. The country's significant government debt, which exceeds 110%, is a key concern. While a figure of 100% is often considered a formal reason for concern, the specific implications depend on the country's circumstances. Furthermore, there are virtually no reserves from which to collect additional euros. In France, government spending already provides 57% of GDP, so there is no scope for further increase. Given this ratio, it is pertinent to consider whether the Fifth Republic can be categorised as a market economy, given the government's substantial involvement in resource redistribution, which exceeds 50%.

On average, an OECD country currently has debt that stands at approximately 111% of GDP, in comparison to around 70% in the mid-2000s. There are no special options to get out of the stupor. While theoretical logic suggests lowering the rate, this would likely result in strong inflation, which has already been barely suppressed. The most extreme measure that Europeans will consider is debt monetisation, should all other options have been exhausted. However, all indications point to the likelihood of this occurrence in the near future. The national debt has become a significant issue, the solution to which is unlikely to be directly prescribed in a school textbook or even in the works of professional economists.