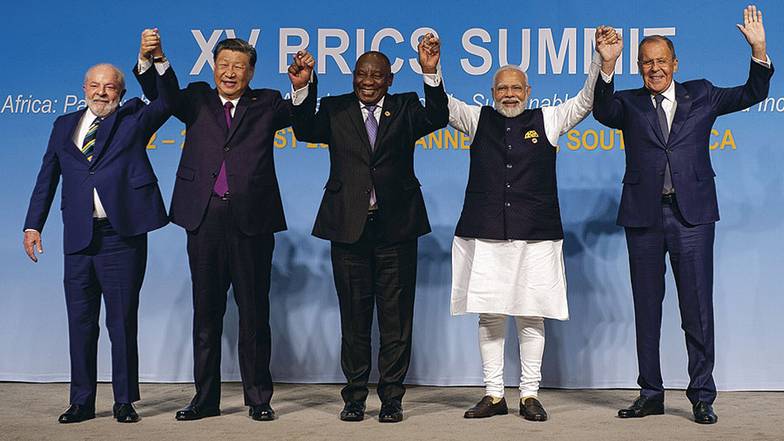

The 2023 “Expansion Summit”: BRICS+ History in the Making

By Yaroslav Lissovolik

The 2023 BRICS summit has clearly been one of the most historic and transformational BRICS summits on record – a major expansion was unleashed by the bloc, with six new members forming part of the BRICS core starting from January 1, 2024: Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt and Iran. At the same time, the BRICS summit Declaration has underwhelmed in terms of the ambition on the economic front as compared to expectations. Some of the key economic priorities, including trade liberalization among BRICS and the progression towards a common currency have not had an explicit or emphatic reference in the final document:

On expansion: six new members form part of the BRICS core starting from January 1, 2024: Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt and Iran. This expansion enables BRICS to cover almost all of the main regions of the Global South, most notably the Middle East that is now represented by Iran, Saudi Arabia and UAE. Perhaps, the only remaining region left outside the core is ASEAN/South-East Asia. Indonesia was discussed as a possible member, but it opted to stay on the sidelines in the end with the possibility of entry in later periods.

On BRICS+ format and the circle of friends of BRICS: in para 92 of the Declaration the BRICS have tasked the Foreign Ministers “to further develop the BRICS partner country model and a list of prospective partner countries and report by the next Summit”. In essence a circle of friends is emerging in line with what was advocated by Brazil. The BRICS+ format is welcomed in the context of South Africa’s presidency, but there is no framework or plan advanced as to how this format is to be further developed.

On BRICS common currency: there is a vague reference in para 45 of the Declaration: “We task our Finance Ministers and/or Central Bank Governors, as appropriate, to consider the issue of local currencies, payment instruments and platforms and report back to us by the next Summit”. Compared to earlier discussions this is less concrete and emphatic, with no explicit reference made to a common currency. Still, the fact that this paragraph made it into the final Declaration allows the BRICS countries to move towards forming working groups to discuss the possible modalities of the single currency for the next BRICS summit.

In the economic sphere, one of the key themes is the greater use of national currencies and there clearly is far more that needs to be done to advance this transition. Apart from the New Development Bank (NDB) that may step up efforts in this sphere there are also the regional development banks, where BRICS and BRICS+ countries are members. Thus far, the BRICS have not exploited the full potential for economic cooperation that resides in bringing together all the regional integration projects and regional development institutions of BRICS and the broader Global South.

As regards the common BRICS currency, Lula is standing out as the champion of the cause, with statements from the Brazilian president emphasizing the benefits of the common currency for trade and investment among BRICS. In particular, Brazil’s leader, called for the creation of a reference unit for BRICS countries—something that is likely akin to an accounting unit that has been discussed at the expert level in the preceding several months. The importance of Lula’s comments is in laying the groundwork for further progress on this front, with increasing likelihood of the R5 project taking off towards the year 2025 when Brazil takes over the chairmanship in BRICS. China may become more supportive of the common BRICS currency in the near term as it may conclude that going solo with only pursuing the internationalization of its own currency may not achieve as much in the way of de-dollarization, with exposure to technological, trade and other restrictions also being a factor to reckon with.

A key area of focus in the coming years should also be the expansion in the mandate of the BRICS New Development Bank as well as the BRICS Contingency Reserve Arrangement (CRA). With respect to the latter, there are several key trajectories that could be explored in view of lacking effectiveness and impact on the part of the BRICS CRA:

-

Coordination of macroeconomic policies on the part of the BRICS/BRICS+ economies

-

Publication of BRICS economic trends and preparation of research materials that identify risks and provide early warning systems for BRICS economies

-

Analytical work on the expediency and modalities of a common BRICS currency

-

Creation of a platform of cooperation among the regional financing arrangements in which BRICS countries are members.

There also needs to be a far more ambitious agenda for the New Development Bank after the BRICS “expansion summit”, with the key near term priorities including:

-

Further expansion of membership with a particular focus on the regional partners of the current members to widen the scope for “connectivity” and regional green development

-

Creation of a common platform for regional development banks, in which BRICS+ countries are members

-

A more emphatic global profile, with active presence in BRICS/BRICS+ summits as well as the annual summits of the G20 group and other key international economic fora

-

Formation of a portfolio of NDB’s “brand projects” that are to deliver a sizeable impact on growth and quality of economic development in the Global South

-

More active progression towards issuing financial instruments and undertaking lending in national currencies

-

Coordination with BRICS CRA of analytical work on the possibility of the creation of a BRICS common currency

-

Greater activism coming from the regional centers of NDB to weave the regional development agendas into NDB’s project priorities

Another key focus area in the economic sphere is trade liberalization—it has not featured in the recent summit decisions of BRICS economies, even though if pursued it may be one of the most important factors that could raise the weight and prominence of the expanded bloc in the world economy. The urgency in trade liberalization coming from BRICS is not only the opening of markets per se, but in providing greater development opportunities to the Global South, including with respect to Africa.

In fact, it is precisely through greater trade liberalization that the BRICS economies can assist the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to become a driver of regional economic growth for Africa. Most of the expanded BRICS+ economies have relatively high import tariffs and there is sizeable scope for a concerted round of trade liberalization that would prioritize AfCFTA members.

The agenda of trade liberalization would open up a number of development trajectories for the bloc that could take its level of economic ambition to another level. In particular, a number of BRICS economies conduct their trade policies via their respective regional trade arrangements: Russia via the EAEU, Brazil via MERSOSUR, etc. A reduction in the level of import tariffs via-a-vis Africa coming from BRICs would necessitate a lowering of import barriers in the regional partners of BRICS core members, leading to a “multiplier effect” in trade liberalization encompassing a rising number of economies from the Global South.

The BRICS+ trade liberalization agenda would accordingly bring the respective regional integration projects of BRICS+ economies towards greater coordination and cooperation, opening new venues for advancing a pragmatic economic agenda. In comparative terms, BRICS economies have far more scope for trade liberalization compared to developed economies—greater market access for Africa and other parts of the Global South may represent a key competitive advantage exercised by BRICS vis-à-vis the G7 economies.

The recent G20 summit in India has, in fact, shown that Western economies will be seeking for ways to build their own bridges to the Global South, most notably through platforms that compete with China’s Belt and Road (BRI) connectivity project. Of note in this respect was Biden’s declaration on the launching of a BRI competitor framework that would include prominent members of the expanded BRICS+ such as India, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. This came on top of the accession of the African Union into the G20—something that will raise pressure on BRICS+ to come up with a clear, pragmatic economic agenda that is appealing to the economies of the Global South. And of course, even after the impressive BRICS expansion in 2023 there remain a number of important economies in the Global South that thus far have not been brought into the orbit of BRICS+ cooperation, including the likes of Vietnam. U.S. President Joe Biden visited the country after the G20 summit and raised the U.S.-Vietnam relations to a level of Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.

All these developments entail that BRICS+ needs to come up with credible and innovative projects for the Global South in the coming years. Postponing the “integration of integrations” path further in favor of piecemeal expansion will eventually lead to diminished enthusiasm from the developing economies to join the BRICS+ project. Expanding the outreach not just to individual countries, but to whole regional blocks, will enable BRICS to work more closely with regional associations such as ASEAN and the African Union. Indeed, the South-Western pocket of the Global South represented by ASEAN is effectively the only region in the developing world that remains outside the BRICS+ grouping. As historic and grand as was the BRICS 2023 expansion in membership, the competitive realities of the global economy call upon BRICS+ to take the outreach to the Global South to a whole different level.

This article originally appeared at brics-plus-analytics.org