XV BRICS Summit and Affirmation of the BRICS Agenda by Country Agency

By Mikatekiso Kubayi

The BRICS bloc was dismissed by many in the beginning, with some arguing that it does not hold sufficient power to change anything, let alone contend with the global hegemons. But BRICS is not about challenging anyone. It is about fostering cooperation and collaboration to find solutions for global challenges and achieve a shared future in which development is enhanced and accessible to all who seek it, Mikatekiso Kubayi writes.

Some Background Reflections

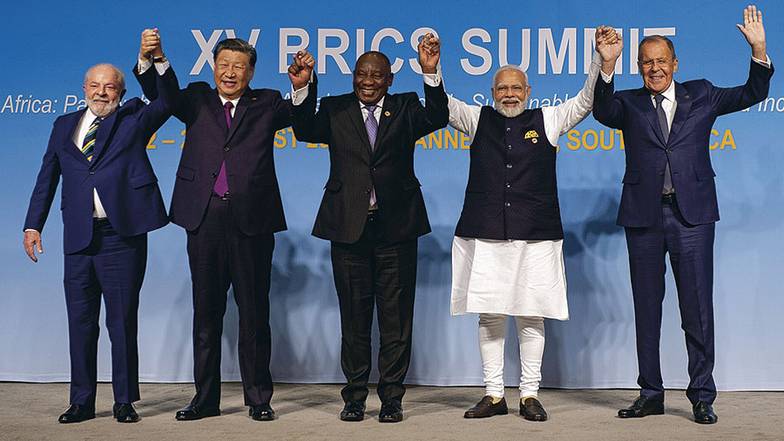

The recently-concluded BRICS Summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, was not only a success for the bloc but also historic in how it captured the times we live in today. The heavy global expectations sat on the shoulders of all those with a role in the dynamics. These main expectations leaned on two central narrative generators: 1) global financial architecture reform efforts (development, payment system, BRICS currency, ‘de-dollarisation’) and 2) BRICS expansion. Aided by country-level agency, the summit went quite far in meeting these expectations.

But what is this agency, and why is it relevant? It is best to revisit the formation of the bloc in 2009 and at least some of the associated dynamics of that time to provide a context for the evolution of the bloc, culminating in the outcomes communicated in the BRICS Johannesburg 2 Declaration. This is important because to assess its advances correctly, we need to recall why it was formed and what it must advance, therefore determining whether the declaration reflects an advance towards the goals and aims enumerated in 2009.

In 2006, the BRIC foreign ministers and finance ministers started meeting to discuss various issues of common interest, particularly their role in global governance. In 2008, the housing market bubble in the United States burst, triggering significant devastation to economies around the globe. Moreover, the developing economies had no role in provoking this, nor had they had a role in the governance of the global financial system or its design. At that time, Africa had one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, along with China, India, and Brazil. Even Russia was experiencing notable growth. Recognising that there was something wrong with the system and the need to expand the representation of voices of developing economies in global financial and economic governance, the G20 was established.

But, of course, this had not been the first global economic crisis. There had been others leading up to this. Many scholars have traced the problem to the very nature of global capitalism, dis-investments in the productive (real) economy, financialization, deregulation, shareholder value (capitalism), and other advice from significant consulting companies since the 1950s. Indeed, the romance with financial markets and the seduction of speculation and quick profits, mainly to make books appear more attractive to shareholders, was real. In 2009, the BRIC bloc of the most significant and fastest-growing developing economies was formed. At its formation, the bloc stated its agenda for reforming global economic governance and its architecture, development, and reform of multilateralism with the United Nations at its centre. The bloc also stated then that it had no intention of replacing anything or anyone. Its agenda was not acrimonious.

In 2010, South Africa joined the bloc. This was a significant development because Africa suddenly had a voice among a group of fast-developing economies. It was also significant in that the BRICS footprint was now extended by population, land mass, and region, along with the influence that came with them. In 2013, several African countries were invited to the BRICS Summit in South Africa. The concepts of a BRICS+ and BRICS outreach were proposed by China and formalised by the bloc. Throughout this period, the effects of the global financial crisis continued to bite, even though the Chinese and Indian economies continued to lead global growth numbers.

On the Reforms of the Global Financial Architecture and Multilateralism

Firstly, the BRICS bloc has consistently reaffirmed the centrality of the United Nations in global governance, particularly in the future of the global governance system it envisages. The bloc has also consistently reaffirmed the role of the G21 (including the African Union, AU) in global financial and economic governance. Most BRICS members, including those of the BRICS +, are members of the G20. There may well be new additions to the bloc announced at next year’s summit in Russia, too, that may also be members of the G21 if the AU is officially announced as a new G21 member in India shortly. Growing the voices and democratizing the governance system have been on the agenda of the bloc and represent a step in the direction of reforms.

The inclusion of oil-rich nations such as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Iran introduces an expansion of the BRICS footprint in the Middle East as well as its influence for the reform of the financial architecture in addition to population, region, and land mass. The Inclusion of Argentina, Ethiopia, and Egypt (Egypt is already a member of the New Development Bank, NDB) further reaffirms the bloc’s growing influence for the reform and development agenda it adopted in 2009. More than 20 countries have applied, and over 40 are interested in joining the bloc. This is a significant development because it demonstrates the strength of the BRICS argument for a fairer and more equitable global governance system that represents all, with rules that apply equally to all, especially in global financial and economic governance.

It should be recalled that the bloc was dismissed by many in the beginning, with some arguing that it does not hold sufficient power to change anything, let alone contend with the global hegemons. But BRICS is not about challenging anyone. It is about fostering cooperation and collaboration to find solutions for global challenges and achieve a shared future in which development is enhanced and accessible to all who seek it. Of course, a change in the global financial architecture is a significant undertaking, and it comes with many challenges, including possible resistance.

Many developing economies want to achieve higher levels of industrialization, and for this, they need significant sums of investment in infrastructure, research and development, manufacturing, and the development of localized value-added production. They also have sizeable dollar-denominated debt as well as a retained natural interest in trade with developed Western economies. The levels of integration of the BRICS economies with all developing economies, especially those interested in joining the bloc, are on the agenda for improvement in pursuit of reform and development. Ministers of finance, as well as heads of central banks, have been tasked by the BRICS Summit to explore payment systems and other facilities for improved and more cost-effective ways of trade, and to report by the next summit in Russia. Decisions may be taken in this regard at that summit.

The Secretary General of the United Nations joined the calls for reforms of the UN, especially the UN Security Council. The Bloc had earlier, in its declaration, announced its support for the inclusion of South Africa, India, and Brazil in the Security Council as permanent members. So, has the Johannesburg 2 declaration lived up to its great expectations? It has gone a long way in doing just that. It has undoubtedly sustained the momentum towards such, notwithstanding the complexities involved in reforming the global financial architecture. The increased use of local currencies in trade between states has already begun and is highly likely to increase. Even the G20 Summit 2022 affirmed the need to grow local currency capital markets.

This article originally appeared at https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/5th-brics-summit-and-affirmation-of-the-brics/